The end of the year is now upon us and by way of wrapping up 2025 here is a bit of light reading for you.

Perhaps due to advancing years, or maybe it is just that I have a bit more time on my hands these days, but I have been reminiscing more than usual about my life of late. For the purposes of this blog I thought I would share some of these gentle meanderings down the dusty byways of my angling past, for no better reason than it helps me to drag some of the details out of my memory. Much of these musings have been aired here in previous posts, but then Frank Sinatra didn’t sing ‘My Way’ just the once. Before launching into this unremarkable piece of digital prose, let me assure you that I am aware how we all see our past through thick rimmed rose tinted glasses, and these accounts of yesteryear are no different. This is how I remember the events of my past, others may have different recollections.

The river Don

I first became aware of the river Don in Aberdeenshire when my father took me with him to find a spare part for his car. This was an ongoing theme as we were a poor, working class family and my dad, lord rest him, owned a succession of bangers as they were all we could afford. This in turn led to frequent trips to the car breakers, know to us all as the ‘scrappies’ where he rummaged around rusting Fords and Austins looking for a distributor or a radiator or whatever was currently malfunctioning under the bonnet of his motor. I, of course, was nearly always at his side during these treasure hunts, handing him tools or an oily rag as required when he was fighting to remove a part (these were the days when you just wandered in and took the part you wanted off the wrecks yourself and paid at the gate. None of your health and safety nonsense). This particular day the usual scrappie, Stanley, did not have the part required, so my father drove along the back road to Dyce where there was another vendor of dodgy second-hand car spares. The road follows the Don and at one point was immediately across the river from the Stoneywood papermill. That day, the mill was obviously making purple paper (it specialised in high quality coloured grades of art paper) and the effluent was pouring out of a culvert and into the river. A blackish/purple cascade dropped 20 feet or so into the otherwise clear water, staining the river downstream as far as I could see. Even at that age I was appalled by the pollution, it looked evil to my young eyes. ‘What’s that?’ I asked my old man. ‘That’s the Don, it is always like’ that he answered and we drove on in search of the elusive carburettor.

Many years later I would leave school and go to work in the papermills. I learned that the wastewater I had seen as a kid polluting the river contained valuable chemicals and between the need to save money and in response to tightening regulations the days of gross pollution by the mills were over. But the Don had suffered gravely over the years and the lower section of the river had been heavily industrialised. Weirs were constructed to divert the flow to generate power or for use as process water. By the 1970’s these barriers, the pollution and the deprivations on man in general had decreased the salmon and sea trout populations to near extinction. Just in the nick of time, the new laws came into force and the remaining mills cleaned up their acts and installed proper effluent treatment systems. Huge sums were grudgingly invested in settling tanks, aerobic digestors and the rest of the hardware required. The salmon came back in numbers over the following years, and I had many seasons of wonderful fishing for them from the same river that had seen being turned purple as a kid.

Long before I ever dreamed of catching a salmon I fished the Don as a nipper. In the company of fellow raggedy kids, I’d explore the disused mill building that lined the lower reaches and sometimes bring my fishing rod to cast worms into the turbid water. These outings never produced a fish for me, but I recall one of the lads catching a flounder which sported a huge growth on its back. Disgusted by the sight of the appendage, the hapless flattie was tossed back into the fetid water from whence it had lately been dragged. Of course my parents never knew their only son was playing in such dangerous places, back then kids were left to run free without the restrictions placed upon them nowadays.

Those formative years spent beside the Don shaped not only my approach to angling but also instilled a deep appreciation for the resilience of nature. The river, once tainted and struggling, had slowly healed, mirroring my own journey of learning and growth. It was more than just fishing—it was witnessing the subtle changes in the landscape, the return of life to waters that had been written off, and feeling a sense of hope every time a salmon leapt, defying the odds. Moments spent in quiet reflection by the riverbank, rod in hand, became a cherished ritual, grounding me in the present while connecting me to the past. This may sound a bit high brow for a working class lad but after a rocky start to life I was finally maturing and opening my mind. Sadly, it feels like so many rivers and loughs are now fighting a losing battle when it comes to pollution and exploitation.

Later, and now the proud owner of a fly rod, I would poach the lower beats trying for brown trout which were by then recolonising the bottom of the river as water quality slowly improved. My best day saw me net four trout, one of them close to the magical one pound in weight, caught on wet flies swung in the fast current of the pools in the Granholm beat. The last of the four trout I can still recall, a dark half pounder landed with the hum of the council waste water treatment plant behind me. Looking back, I suspect the ghillies saw me and let me off as I was just a kid and not their nemesis, the professional poachers who netted the river on a nightly basis. Needless to say, we never ate any of the trout we caught from those less than salubrious reaches of the lower Don.

By the time I had reached my early ‘teens I had graduated to the Kintore beat a few miles upstream. This entailed an early rise, a brisk walk down the hill, resplendent in thigh waders and a smelly parka which should have been thrown out but was retained solely for fishing days. I’d catch a ‘country bus’ at the foot of Anderson Drive and get off in the village of Kintore where I bought a day permit from the local newsagents shop for a few pence. Kintore was a better salmon beat than a trout stretch. The river was deep and slow, the banks high with very little in the way of cover to mask your movements. This was another tough school to learn in and I blanked most days I fished here. While there was some fly water most of the time my spinning rod was in use. Spoons, particularly the deadly ABU Toby, were expensive and losing one on the bottom was a traumatic experience. I persevered and managed a few trout, even catching my first trout on the fly one spring day, but I knew I could be doing better.

Kintore was OK, but I heard from other kids that Inverurie, just a couple of miles further upstream was a better beat to fish. Here the river Don was joined by its main tributary, the river Urie. A smallish stream, to flowed in from the north, passing close to the eastern edge of the town. The same bus took me there and permits could be bought from the grocers shop in the triangle. Then it was a walk down the main street lined with low granite houses and small shops and a left turn on to the back road to Oldmeldrum and through the graveyard to the banks of the river Urie, where I was to spend so much of my youth.

The Urie rises to the northwest of Bennachie, the hill that dominates the Aberdeenshire countryside around Inverurie. Its main tributary is the famed Gadie Burn, celebrated in the old Scots song ‘Bennachie’. In my day the Urie was stuffed with wild brown trout, mainly small fish of half to three quarters of a pound but with the odd better fish too. I’d fish there every Saturday during the season, accompanied by such luminaries as Ashly McKinnon, Mike Gibson or Alan Robertson. As I improved my casting and general watercraft so my catches became more consistent. We would set off armed to the teeth with a fly rod and a spinning rod each, a box of flies, another of spinners and (may the good Lord forgive me), a tub of maggots bought the previous evening from Brown’s tackle shop in Bridge Street.

Usually I would start with the fly and fish wets through the runs near the graveyard, before doing a bit of maggot drowning in the slow water above the joinings pool. Hopefully, there would be a hatch of olives, iron blues or march browns which began around midday, and I aimed to be at the head of the Joinings for that event. Wading in the fast water was exciting and I had one or two duckings for being too optimistic on the slippery bottom, but we caught a few lovely trout there. The rest of the day was spent moving up the Don, as far as the black pot where the locals were hurling devon minnows into the deep water in the hope of a salmon. I only ever saw one being caught there, a fine ten pounder which was hooked on a red devon by an old fella who was ecstatic at his success. These halcyon days felt like they would never end, me and my mates laughing and messing about and catching a few trout in the warm spring days of quiet, rural Scotland. Falling in while trying to retrieve a Mepps stuck in a tree branch, the day when there was a huge hatch of olives and I could do nothing wrong, hauling in trout after trout on a dry fly which fell apart eventually. The tiredness as I sat on the bus home and knowing I still had to walk up the long hill to Larch Road once I got off the bus. The longing all week for Saturday to arrive and I could set off again for Inverurie and the spotted trout I loved to catch. I could argue that those far off days were the most wonderful of my angling career.

At the ripe old age of fifteen I was accepted to join the Aberdeen and District Angling Association (the ADAA). This was a transformative moment in my angling life. My parents helped out with a few bob towards the entrance fee as I was still at school and surviving on pocket money from them. Overnight, the possibilities for fishing exploded and chief among the veritable cornucopia of venues were the beats on the river Don. The ADAA has expanded considerably since those far off days, but back then they owned the rights to the Upper Parkhill beat which stretched from the road bridge at Dyce up to the top streams above the old graveyard. I would haunt this part of the river for years, getting to know it intimately as I learned my craft as an angler.

Parkhill was not an easy beat. The main issue was the angling pressure as it was close to the city and thus very busy at weekends. It was normal to see rows of anglers fishing when the salmon were running and arguments were common when someone would try to cut in too close to somebody already fishing. The lower portion of the beat comprises of long, slow, deep pools while the upper section is better fly water with runs and pools. Back then, there was a meat processing factory next to the river, Lawson’s of Dyce. A small stream ran from the plant to the river and you had to hop across the trickle of water which ran red with the blood of the pigs slaughtered just yards away. Salmon were scarce but not unknown, though as a kid I was just interested in the trout. Fly and spinning were both allowed and I utilised both methods to begin with, gradually dumping the spinning rod as I grew older in favour of just my fly rod and a box of flies instead of a bag full of gear.

At aged 17 I left school and got a job in the Mugiemoss mills, working shifts on the factory floor. The management decided to send me to college and so I was packed off to the Aberdeen technical college three times on 10 week blocks of studies. When not at college I was used as a spare production operator, slotted into wherever there was a gap, such as if someone was ill or on holiday. I learned how to operate every conceivable sort of machine and worked with a range of characters. Hawkeye, the re-reeler man worked permanent night shift and was put on with him for a few weeks. He His nickname came from the fact he had lost an eye in the war and he derived great joy from removing his glass eye and putting into his assistant’s mug at tea break. That re-reeler was in a big shed next to the river and at night the rats would scuttle across the floor and nick your sandwiches if you left them out.

The mix of working in the mill and then studying at college was a double edged sword. You see when I was working shifts I had lots of time to go fishing, while the 9-5 of college severely curtailed my piscatorial ventures. Mind you, there were compensations for the loss of my angling, in the shape of socialising, drinking and of course, chasing the fairer sex. I also bought my first motorbike, opening up a whole new world for me. I did OK at college, despite falling asleep at my desk most afternoons after pints of beer downed in the Blue Lamp pub every lunchtime. The Blue Lamp had an ancient jukebox which only had hits from the ’60 on in. Any time I hear the Doors ‘Rider on the Storm’ I am transported back to those boozy lunchtimes in that cool, dimly lit lounge just down from the college.

My main reason for going to work in the mill was they had the fishing rights to a short but productive stretch of the Don. This single bank mile of water included pools such as the big Stane, the pipe, the Saugh and the Millionaires. By sheer luck, I commenced working in the mill just as the salmon runs made a recovery, meaning I had a few seasons of excellent fishing, all be it in very industrialised settings. This was spinning water, deep and powerful, but I did manage a few salmon on the fly rod. The bottom of the river was treacherous with big rocks and industrial debris littering every pool. Tackle losses were huge, so we tried to mitigate this expense in various ways. We bought ‘Dibro’ plastic devon blanks in bulk, then painted them ourselves and made our own mounts. Then someone decided to try fishing with tube flies on a spinning rod. These worked a treat and we could make them up for a few pence. The tubing came from the outer plastic sheathing of electrical cables, of which there was a plentiful supply in the mill. We didn’t bother with a body or rib, just some hair whipped on to the tube as a rough sort of wing was all that was required. A Wye lead, made ourselves after we bought a mould, was tied two and a half feet above the fly. Thus a two inch tube fly cast on a spinning rod rapidly became our favourite method of catching salmon. My own best day saw me land five springers, a feat which seems unreal in these days of reduced runs. Many of the lads I fished with caught twice that number some days.

I still fished Upper Parkhill of course, both for salmon and brownies. Summer evenings were a joy, the trout coming on the feed as the light faded and requiring perfect technique if you were to fool one. The smell of wet grass, a gentle hum of flying insects and the occasional heavy splash as a trout slashed at a hatching caddis were scenes played out in front of me on so many evenings. By now I owned a dodgy Ford Cortina, so travel to and from the fishing was a breeze, even if I was now visiting the same scrappies as my father did!

There were days of salmon fishing when the great silver fish responded to my fly or spinner. A memorable sea trout (my first ever) hammered a size 0 gold Mepps just as the light faded and fought like a demon. The spring days when trout lifted silently from the bottom to examine my dry fly, only to turn away in distain at the last second. My great joy was wading to try and get to places nobody else could. This of course led to frequent duckings, but I never learned my lesson and I was often to be found in the strangest of places in the middle of the river, soaking wet but grinning like a cheshire cat as I cast to rising trout in the afternoon sunshine. The Blue Dun, Ginger Quill, March Brown, Greenwells, Badger Dun and the Dundee Special were my favourite flies back then with the Wickhams a great pattern for the darkness of a summer night.

I grew restless working at the Mugiemoss mill. The management had decided that my poor timekeeping and attendance was getting out of hand so they put me on to the same machine (a Black Clawson reeler) as my father, obviously in the hope he would keep me in line. Well, that didn’t work out and I found a job in another mill down the river a few miles. Starting off in the QC laboratory I progressed to the factory floor and, remarkably, the mill sent me off to university. I spent the better part of four years working there and completing my studies, all the time fishing my beloved river Don. The mill had the rights to the fishing on the river immediately behind the factory, so I fished there fairly often. It was not a great beat, the salmon tended to run through in all but the very highest of spates. I did land a few, including what would turn out to be my biggest salmon, a fish of 24 pounds.

The river Ythan

I had first fished the Ythan when I was still at school. The small river ran through the town of Ellon and you could buy a day permit to fish there for a small sum. While there are a few small brownies in the Ythan, it is a sea trout fishery (or at least it was). The fishing season opened on the 11th February and the river would be full of finnock and sea trout kelts. For those unfamiliar with sea trout, the parr turn to smolts (we knew these tiny fish as ‘yellow fins’ in Aberdeenshire). The smolts migrated to the sea and returned as finnock, bright, silvery fish of between a half a pound and a bit more than a pound. Finnock continue to feed in fresh water and only a small percentage of them spawn. In the springtime the finnock drop back down to the sea in the company of any surviving kelts. They return as full grown sea trout the next year and this time they spawn during the winter months.

The kelts obviously went back but the finnock did not spawn and so you could keep them as long as they were above the legal size limit. By the end of April the kelts and finnock had all dropped back into the sea and the fishing ground to a halt. A summer spate would bring a few sea trout in but it was really the months of September and October which were the high point of the year. Each tide brought more bright silvery trout in and these were fish of between a pound-and-a-half and four pounds. At Ellon the river is narrow and deep, not great for the fly and so we wormed it. A few split shot and sometimes a twist of red wool on the line as a marker above a size 8 hook baited with a lobworm made up our tackle. You would cast out then slowly walk downstream, keeping pace with the worm and striking at any slight pull or drag on the line. I was never that good at this method but some lads were lethal with it and huge bags of sea trout and the occasional salmon were taken. I did catch enough to keep me going back on those days when the river was big and brown with flood water and the red dot of worsted vanished suddenly as a trout swallowed my worm. I look back at those days and wish I had learned to trot with a float, I’m sure I would have caught many more trout!

I was fishing the worm one autumn day at Ellon when I met with two other young anglers. It had been a poor day so far with only a couple of missed bites between the three of us. The other lads were debating whether to go to the Macher Pool, as they were, like me, members of the ADAA. I had never been there, simply because I had no idea where it was. For younger readers, this was long before the internet and google maps, let alone mobile phones. The two lads had fished there before and were prepared to show me where the fabled pool was. Catching a bus at the bridge, we were soon deposited a couple of miles out of town and started to walk down the hill of a narrow country road. One of the boys suggested a short cut if we hopped over a fence and across the field. In attempting to jump the barbed wire fence I slashed my new thigh waders just above the knee, totally ruining them. This was nothing sort of a disaster and worse was to follow. Gaining the pool, we found perhaps 50 anglers hard at it, some spaced out across the low, shallow part of the tidal pool, the rest in a line, shoulder to shoulder. These were the wormers, intent on the merest twitch of their line which signalled a salmon or trout. It became apparent that my ripped waders meant I could not get out to where the fly fishers were having some sport, so instead I trudged off up to the far end of the line of wormers and started to fish like then, only from the edge due to my leaky boots.

Fish were being caught every few minutes on the worm. A fella would let out a shout and, without winding in, walk backwards on to the shore and drag a protesting sea trout out to be whacked on the head. Every now and then a more excited shout went up as some lucky fisher bent into a salmon, requiring those in his immediate vicinity to vacate their spot while the battle went on. I watched all of this in awe, I had never seen fishing anything like this. Finally, my own line tightened and I lifted into a nice sea trout. Following the example of those around me I bullied the fish out and up the shingle. That would be the only fish I touched that day, but I fell in love with the Macher pool. I know that these days it is but a shadow of its former self but I remember those days of hard fighting sea trout and the smell of the salt on the wind, the fresh fish leaping as they came into the pool.

Fly fishing on the Macher Pool was a very precise business. A floating line, a cast of two flies, those being tied on size 14 or 16 double hooks. Patterns were almost exclusively Cinnamon and Gold, Dunkeld or Grey Monkey. You would fish the tide down, from about halfway, through low water and then back up as the tide came in. It was believed that the trout ran through the pool and up the river in high water, but I always had my doubts about that and I think that while some of the trout did that, others either stayed in the pool or dropped back down as the tide receded. The wind was a menace, frequently blowing a gale and making it impossible to cast or dying away to a zephyr allowing the trout to see your every move. A cloudless sky was a disaster, and I spent many, many hours looking up at an azure sky in the hope of seeing a cloud.

My best every sea trout came from the Macher Pool. It was July and there had been some rain. I took it in my head to try the Macher, even though everybody knew it would be another 6 weeks before the sea trout would show up in numbers. I was running about on a Kawasaki 250 at the time, so I hopped on to her and thrashed my way north along the well ridden roads to the stoney car park above the pool. A couple of other anglers were already there, fishing the worm in the still too high water. I recall taking my time tackling up as the tide would have to drop a bit more before I could wade in far enough to fish. At last, I walked down the path to the bench, left my tackle bag there and waded out into the cool water. My leader was 5 pound breaking strength nylon and a dunkled with a teal wing was tied on to the tail (I can’t for the life of me remember what the other fly was). I lengthened the line, the wind coming across my right shoulder making it hard to get more than 15 yards out. Maybe 20 minutes passed before the line tightened and I was into a sea trout of a couple of pounds which was duly netted, dispatched and stuffed into my fish bag slung on my hip. Back in action again, I took a few steps downstream and cast at 45 degrees, the best angle I could manage in the wind. Only a few casts elapsed before the rod was almost pulled out of my hands and a very big sea trout rolled at the end of my leader. The fight was a mad encounter as the trout tore line from my reel with vicious runs or splashed close to me in a way which suggested he was not that well hooked. I netted him in the end and waded ashore before taking him out of the meshes. He weighed in at five and quarter pounds, more than a pound heavier than my previous best. While that would be the highlight of the session I managed a further three trout, making five good fish before the tide turned and flowed strongly around my chilled legs, telling me it was time to head for home.

I mentioned my ‘fish bag’ there. These were carried by all Ythan anglers back then. Homemade, they varied in design, dimensions and materials used, but we all had one. Mine was fabricated from an old plastic fertiliser sack which I cut down to size. I made it one night when I was on night shift in the mill. It was a slow night and I had time to fiddle about making the bag when the supervisor was not around. The bag was fitted with a rope sling, fashioned from ‘machine rope’, a nylon hollow braid used on the feeding mechanism on the paper making machines. I stitched the rope to the edges of the bag and added a large split ring so I could hang my landing net on it. That bag saw many years of hard service, only being thrown out when my wife objected to it coming into the house when we lived in Ayr. In fairness to her, it did stink to high heaven. I should have cleaned it up and hidden it from sight but instead it was consigned to the bin, a sad end to such a faithful bit of kit. Back then, we thought nothing of making our own gear, there wasn’t the money around to buy stuff and if you could make something then you jolly well did. How times have changed!

The ADAA also had the rights to another stretch of the Ythan. Far upstream near the hamlet of Methlic, they had two miles of single bank sea trout fishing. This was much like the water down river at Ellon, slowish, deep water that fished best after a spate. Loved this beat and had some great days on the fly, especially very early in the season. In many ways this was easy fishing, you didn’t need to cast long distances, the banks were relatively clear and the beat was rarely busy. My favourite flies were the Malloch’s and the Grey Monkey, both of which were tied on the smallest double hooks I could find. Some of those flies from that time are still in my fly boxes! Again, I hear this beat is nothing like as productive as it used to be in my day.

All change

It was the usual story, boy meets girl, boy marries girl, boy hardly goes fishing any more. We bought a tiny flat on the edge of the city and worked hard at our respective jobs to keep the money coming in (this would be around 1984 or so). Fishing just became harder to fit into my busy life somehow. Then, in 1988, I joined a Finnish company who were building a new mill down in Ayrshire and my life shot off on a totally new trajectory. I was required to go and work in Finland for a while, so all our goods were packed away in storage, she moved into a hotel near Irvine and I prepared to be shipped off to Scandinavia. Drives between Aberdeen and Ayrshire fetching the last of our bits culminated one September day and my faithful Volvo 245 pulled up the hill south of the town I looked in the mirror at the city of my birth for the last time as a resident. My rods, reels and other paraphernalia would not see the light of day for a couple of years as I was either abroad or working extreme hours as we battled to start up the huge manufacturing complex. I started out as a shift supervisor and was promoted to a day shift job as a technical supervisor. We bought a rambling old house in Ayr which needed a lot of work, but I enjoyed spending any free time (and money) on doing up the building. No sooner had I completed the renovations then I was headhunted for a Production Manager role over on the other side of Scotland near Alloa. We upped sticks yet again, leaving the lovely house in Ayr and buying another wreck of a house near Dunfermline.

My continued absences took its toll and the marriage fell apart, leaving me with house to be fixed up, a complex and demanding job at work and a sense of unreality about how I had come to this. I threw myself into work and the house while at the same time getting back into not just my fishing but also my love of hillwalking and climbing. Looking back, I was living life at an unsustainable pace, long hours in the mill, on call 24/7, fishing or climbing when not working on the house and, after about a year totally alone, socialising at weekends in Dunfermline, Edinburgh or Glasgow. Life for a couple of years was exhilarating and exhausting in equal measure.

Around that time a lot of my fishing was on the lochs and put-and-take fisheries in the central belt. Loch Leven, loch Fitty, Swanswater, Heatheryford and many others were my playground. My fishing gear was usually in the back of my company car so that I could head to the loch straight from work. I fished a lot with Iain Bain, mainly on Fitty, and we made some impressive catches on summer evenings. I met my mate Chris Hall soon after I had started in Alloa. He was a coarse fisher, but I dragged him out fly fishing and he took to it like a duck to water. I showed him the places I fished and even persuaded him to join me on jaunts to Ireland and Orkney.

Back then, fishing for rainbows was still gaining popularity in Scotland and I was like a sponge soaking up the new ideas and methods. Even on the days when I blanked, I always learned something either by my own experiences or by watching and talking to other anglers who were more successful. One of my favourite loughs was Butterstone, a gorgeous fishery in Perthshire. Many days were spent drifting the wooded shores and catching plump rainbows. Some days it was sinking lines and stripped lures, other days small dries or nymphs were better. Ospreys caught fish close to the boat on occasion and the beauty of that lake never failed to amaze me.

Another venue I fished when I lived in Fife was Gartmorn Dam. This was stocked with brownies and was a demanding water to fish. The local usually spun for the trout but I stuck to my flies and had some great days wading out and casting to rising fish. A day off would often find me fishing Gartmorn early in the morning, then heading off for an afternoon hiking among the Ochill hills.

My restless nature meant that I could not settle down in Scotland. The old house was totally renovated by the summer of 1997 and I should have just sat back and enjoyed the fruits of my labour. By then I was working in Aberdeen but living in Fife, so my commute to work was close to two hours drive each way. On one of my frequent holidays to Ireland I had met a girl and decided my future lay across the Irish Sea. The fishing tackle was packed up once again. Some of it came with me when I left Scotland in November of 1997, but a lot more was left in my mates shed along with my other belongings. In the near thirty years since I emigrated I have fished the odd day here and there when holidaying in Scotland, but the fish filled days of my youth are but memories now.

Fly tying

I have detailed elsewhere in this blog how I started tying my own flies as a kid. From the first day I loved making fishing flies and though circumstances meant that through the course of my life there were times when I was rarely at the vice, I always enjoyed any time spent tying.

Initially, I learned to tie without a vice, holding the hook in my left hand and winding the materials with my right. Looking back, this was a great way to learn as it taught me so much about tensioning the tying silk. Without a vice you feel the tension not only in your right hand but in the left too. I didn’t even have a bobbin holder back then either, the wooden spool of Gossamer silk just sat on my lap and I half-hitched each time I went to tie in or wind materials. I progressed rapidly once I had a small vice and by the time I was 14 I was tying flies for the local tackle shops. This was repetitive and boring as the shops used me to make the flies they could not source elsewhere. Sea trout flies tied on small double hooks such as the Cinnamon and Gold and Grey Monkey were staples. When Jim Somers got in a load of size 18 hooks I was tasked with tying Greenwells, Ginger Quills and the like on the tiny Mustads. Of course, it was a win-win for the tackle shops as any money I made from the flies I spent on fishing or fly tying gear.

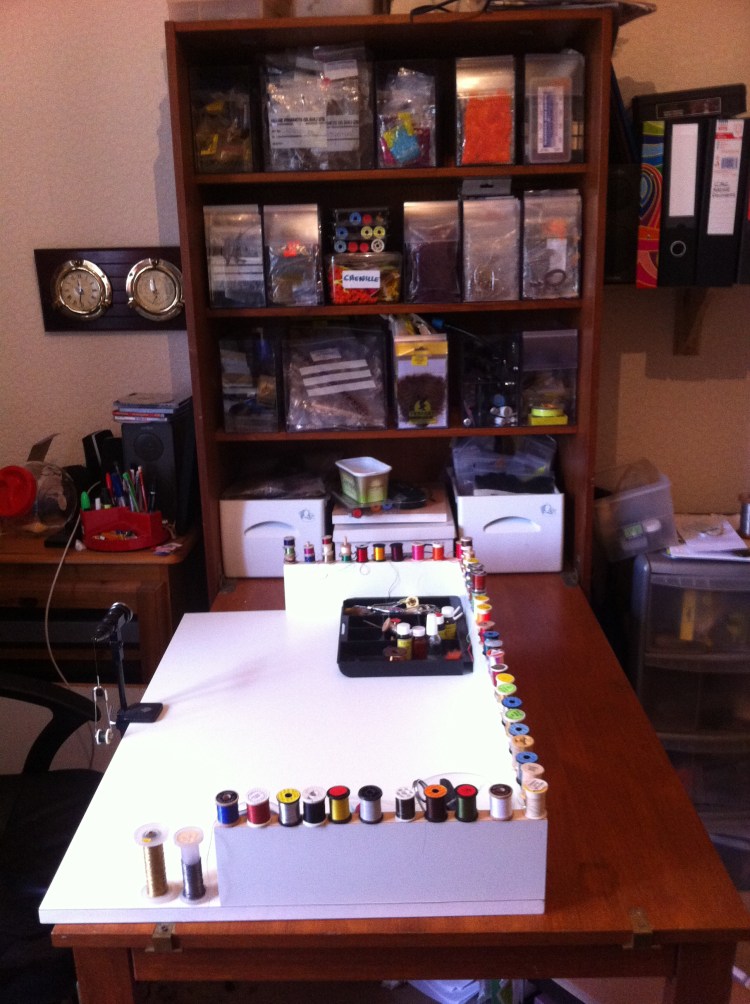

The tiny flat we bought in Bridge of Don was fully furnished. It was pretty poor quality stuff in general but one piece of furniture stood out for me. An ugly looking press which unfolded as a table stood in the minute living room. It really was an awful looking thing and most of the neighbours in the surrounding flats got rid of it at the earliest opportunity. When we moved away to Ayrshire I took the horrid press/table with me and when we finally settled into the house in Ayr it became my fly tying station, a role it has fulfilled to this day. Much battered and chipped, it has seen the creation of many thousands of flies over the decades. All my materials are stored on its shelves and the table part is the perfect height for my vice. I have added small containers for holding various materials and periodically I rearranged things to try and make it more ergonomically friendly. As ugly as it is, this press was a godsend to me and it gave me a lifetime of joy (see below)

The contents of the fly tying press would make your head spin, crammed as it is with a life time worth of fur and feathers. Not one to spend excessively, there are very few premium grade capes and only small sections of precious jungle cock. There are lots of game bird feathers, furs from various wild creatures and an endless supply of weird bits I have picked up along the way. Shooting friends have contributed with woodcock, pheasant, duck and goose feathers. For many years I was tying semi-professionally and bought my hooks and materials wholesale from Veniard. I even went as far as applying for and gaining an import licence and bought capes direct from a supplier in India. Sadly, I let that licence lapse many years ago, but I recall the excitement every time a box turned up from India. I could not order specific capes, you just said how many you wanted and hoped for the best! The contents of the battered cardboard boxes, which stank of camphor, were a mishmash of different colours. Some were poor quality, but there also some gems. There was a vague plan to set up a fly tying materials company but I lacked focus back then so I ended up using the materials myself.

I mentioned that some of my materials came from shooting friends. One in particular worked with me in the mill in Aberdeen. Every inch a countryman, he hunted rabbits with ferrets and was a keen shot. I asked him for hare’s lugs but all he ever brought me were rabbits’ ears. Turning up for a night shift one weekend, Rory approached holding a large, blood stained sack. ‘Here ye go’ and he turned on his heel, leaving me to gingerly open the bag to find a dead fox. Now fox fur is not a widely used material but I figured I had one now, so I had better do something with it. I decided that the best idea was to skin the animal. Waiting for a quiet spell late on in the night, I went behind the machine to where there was a large drain and I proceeded to skin the fox. While halfway through this gruesome task the Production Manager poked his head around the corner and asked what the hell I was up to! There had been a problem in another part of the mill and he had been called in, so while on site he took a walk around and found yours truly butchering a fox. Let’s just say it was not my finest hour! Footnote – a fox skin goes a long, long way and forty plus years on I still have some of the deep reddish pelt.

Later in life I was working away from home mainly, so to entertain myself I would go on eBay and look for bargains. This provided me with glorious opportunities to invest in a wide variety of fly tying crap. I developed a particular fondness for ‘job lots’ of used materials or fishing tackle. These were almost universally badly photographed and lacked any meaningful description, but that was a large part of the fun – I never really knew what would turn up in the post! Some items were rubbish and consigned to the bin, much of it was a mix of good stuff and crap and there were the odd diamonds in the rough. A fiver once bought me a box of fly tying materials, mainly useful but not extraordinary, thing like pheasant tail feathers, hackles of different colours and spools of threads. At the bottom of the box was a tin and inside there were hundreds of Kamasan hooks, most of them brand new and unused.

Sorry to say that eBay became the source of much of my cheap coarse fishing tackle when I took that form of fishing up, and the temptation of so many ‘job lots’ of floats, feeders and all manner of other bits and bobs led me to buy far too much gear. Some fellas have a mid-life crisis and spend their money on red sports cars or dangerous blondes, so my collection of old wagglers may not be such a folly after all.

Best wishes to you all and I hope 2026 brings you health, happiness and a few fish.

Claretbumbler

That was a very enjoyable read, it certainly passed the time.very well whilst waiting in the line of cars to board the ferry at Cairnryan after my Christmas trip to visit my mother in Tynesid. It’s allways nice to hear how fellow anglers started out on their piscatorial journey. A happy new year to you, hoping 2026 is your best year ever!

LikeLike

Hi Andrew, glad you enjoyed the post. Anything that passes the time in that queue in Cairnryan has to be good! Best wishes and tight lines for the coming season.

LikeLike